Adam Mazur

SUBJECTS OF GENDER AND DESIRE

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE COLLECTION OF JOANNA AND KRZYSZTOF MADELSKI

ACT I – THE COLLECTION

Joanna and Krzysztof Madelski have been collecting contemporary art for over twenty years, and Polish postwar photography for three. The theme around which they have been building their photographic collection is femininity, understood in accordance with Judith Butler as a series of performative acts. Photographic nudes, underlying which there is no absolute gender identity, but which rely instead on a continual re/construction and reinforcement of multiplicity, the weakening (rather than expression) of identity. Butler’s Gender Trouble, which is generally well known, but too little read in Poland, provides the starting point for the collection’s premiere. The exhibition’s title is a paraphrase of the Polish title of the book, which was published by Krytyka Polityczna. The Subjects of Gender and Desire exhibition will feature masterpieces of photographic art by classic contemporary female artists, such as Natalia LL, Ewa Partum, Alicja Żebrowska, Marta Deskur, Jadwiga Sawicka, Barbara Konopka, Teresa Gierzyńska, and Katarzyna Gorna, as well as works by representatives of the younger generation, including Aneta Grzeszykowska, Agnieszka Polska, and Anna Senkara. The collection also includes pieces by prominent male artists who have taken up the subject of gender – from experimenters like Marek Piasecki, Zbigniew Libera, Jerzy Lewczyński, Łódź Kaliska, and Mauricy Gomulicki, to clas- sic names in fine-art photography like Tadeusz Rolke, Edward Hartwig, Paweł Pierściński, and Wojciech Prażmowski, and young artists such as Mateusz Sadowski, Maciej Osika, and Jan Dziaczkowski.

An exhibition at the Łódź Municipal Museum was the premiere showing of the collection. It contrasted the way the artists view and analyze the construction of gender, with some more critical than others, but it also contributed to the discussion about the necessity for rewriting the history of photography in postwar Poland. The exhibition juxtaposes the renderings of conservative photographic artists who took part in exhibitions like the Venus International Salon of Art Photography, with the work of male and female artists interested in destabilizing – especially after the changes in 1989 – the exceptionally strong hetero-normative matrix that structures Poland’s culture, including its photography. The multiplicity of techniques employed – from those aimed at achieving elegance to avant-garde experiments, from classical barite prints to contemporary digital photography, installations, objects and video – means the exhibition also offers something interesting from the formal and technical side to those attending the Łódź Fotofestiwal.

ACT II – THE EXHIBITION

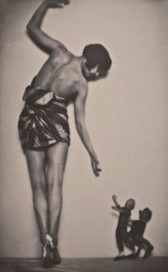

The exhibition Subjects of Gender and Desire is arranged chronologically. The narrative begins in the years before the Second World War, with works by Anatol Węcławski, Józef Rosner, and Benedykt Dorys that are beautifully made, elegant and sensual. The elegance of their technique goes hand-in-hand with the bourgeois conservatism of the treatment of their subject. The postwar period brings a shift, first in the guise of socialist realism, which was for a period of time forced upon Polish photographers, and later by the continued development of classic themes in a form that is more modern, yet which at times is expressed coyly, in a bourgeois manner. The exhibition is constructed linearly, but within it there are turning points, interventions and leaps that provoke questions about the contemporary interpretation of historical photography. The gallery’s two floors provide an opportunity for visitors to become acquainted with the works of both men and women, to observe the process of emancipation and the achievement of self-awareness by fe- male artists, who in the 1970s took the initiative and began to dominate photography, giving it completely new, previously unknown meanings, and using it to express new content.

The exhibition in the gallery on the ground floor begins with some major names in postwar photography such as Tadeusz Rolke, Zbigniew Dłubak, and Jerzy Lewczyński, but it also includes leading female artists, such as Krystyna Łyczywek and Ewa Partum, who move the viewer towards a more critical approach to the topic, going beyond mere affirmation and eroticization (although their classic works, retrospectively la- belled“feminist art”somewhat against their will, are not free of this, either).

The exhibition is divided into sequences of works displayed singly, or merely indicating the presence of a given artist in Joanna and Krzysztof Madelski’s collection, as well as whole bodies of work representative of the creative output of a particular artist. Among the more broadly represented artists are relative unknowns, such as Michał Sowiński, controversial figures, like Paul Pierściński, and artists prized by the contemporary art world, such as Jerzy Lewczyński. Similarly, the narrative exhibition, organized on the second floor, where in addition to selected works by Monika Zielińska, Maciej Osika, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Marta Deskur, and Jadwiga Sawicka, one can see sketches – an exhibition within an exhibition – allowing one to delve deeper into the work of the Katarzyna Górna, Teresa Gierzyńska and Natalia LL. On the ground floor, photography from the past dominates, treating the subject of the nude (“the fairer sex”) relatively conservatively; on the upper floor however, we encounter the efforts that have been carried on with intensity since the 1990s to deconstruct and demolish existing oppressive and stereotypical models of femininity. The androgynous heroes of the photographs of Zbigniew Libera, Maciej Osika, and Barbara Konopka reveal subjects that have previously been excluded or absent – difference, otherness, conventionality – challenging the existing binary order (previously the only transgression was that women sometimes took photographs). Women artists associated with body art and critical art, such as Katarzyna Haute, Alicja Żebrowska and Monika Zielińska (Mamzeta), critically address femininity in its patriarchal understanding.

The exhibition can be seen as a salon exposition, as pastiche, and a further attempt at reworking the traditional Polish means of displaying photographs in “salon exhibitions”, but it can also be viewed as a collector’s study, an office used for studying, devoted to the contemplation of things that are not so much curiosities, as they are valuables.

ACT III – POLISH VENUS YEARS LATER

The genesis of the Łódź exhibition dates back to the Polish Venus exhibition, which I was asked to organize in 2008 during Kraków’s Photography Month. After the exhibition, I began working with Krzysztof and Joanna Madelski, talking with them about the shape their photography col- lection was taking. We shared a fascination for the subject of the nude and a desire to break the impasse in which the photographic nude – and thinking about the body, corporeality, and gender identity in general – found themselves in Polish visual culture. At the same time, we were aware that their efforts to build the collection could not only help individual artists to make further progress in their creative work, and ensure that the achievements of engaging photographers like Michał Sowiński would be noticed, but that it could also allow people to better understand and appreciate marginalized masters like Teresa Gierzyńska and Ewa Partum. The Subjects of Gender and Desire exhibition is much calmer than Polish Venus, being rooted in history and the study and observation of the developing collector’s market for photography in Poland. The result is more of an academic reflection on the ways of representing femininity, and not merely an eruption of contemporary nudes, full of surprises, based on a survey of the work male and female artists are doing in the area.

ACT IV – HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Everyone remembers Venus. Not everyone saw her; some people only read about her in newspapers, while others caught a glimpse of her on a newsreel in the cinema. Organized annually, though with periodic breaks (as was common in the Polish People’s Republic), this exhibition of female photographic nudes was not only a sign of the relative liberalization – moral, as well as political – during the era of Comrade Gierek, it also went down in the history of Polish photography as one of the most controversial and best attended exhibition projects1. Memories of travelling to it with friends from the army in one of the carriages that were specially added onto trains for the event, and attempts by minors to get by the “gate” placed in front of the exhibition, mix with those of official announcements about the theft and destruction of works being exhibited, and later of the court cases related to these events. There were crowds in the gallery, and a tempest in the press, but what exactly caused all this ferment? When you look from today’s perspective at these slightly erotic, but essentially prudish pictures with their pretensions to being art, you can understand how impoverished the visual culture of the former era was, and how the means of visual arrangement has changed over the last several decades. Today, the photographs from the historic Venus salons are no longer shocking, or even titillating. It can even be argued that today the structural equivalent of what they produced are the decorative“soft”centrefolds of“men’s mag- azines” (especially in Playboy, which is known for its artistic ambitions).

The fuss over Venus shows that the lack of beautiful naked women’s bodies was even greater in the Polish People’s Republic than the demand for household items and other essentials. Until a sexual history of that era is written, we are limited to conjectures about the libidinous economy of this particular system. Ewa Franus has written an interest- ing analysis of it based on one of the key paintings in the postwar era, Wojciech Fangor’s Figures (Postaci, 1950); she believes the artist found himself“trapped in femininity”2. The whole of socialist Poland found itself ensnared in such a trap, caught between the communist ideal of the desexualized worker and the “vamp”, that is, the woman as an object of desire. Perhaps the failure of the Polish People’s Republic resulted from the system’s inability to generate a surplus of erotic pleasure, which forced it to rely on a capitalist model3. In other words, the first reprints from Western fashion magazines featuring images of beautiful women called into question, writes Franus, “the authenticity of its proposal for a new codification of the meanings of the female body”(from a female tractor driver or worker to women officials and teachers).

Organized since the late 1960s, the Venus salons can thus be seen as an attempt by Edward Gierek’s new regime to develop a “sexier”, more attractive image for itself. It no longer had a“human”face, but the face of a beautiful woman. In other words, even the Polish People’s Republic was unable to resist the temptation to “commodify” and gradually saturate the female body with sex (and, to a lesser extent, the male body, bear- ing in mind the regime’s “handsome faces”: Cybulski, Wilhelmy, Lapicki, Zapasiewicz, Zelnik, Mikulski). The pleasure of looking had been partially liberated after years of restrictions and limitations imposed by the puritanical morality of the authorities during the Bierut and Gomulka eras. The program for modernizing socialist Poland proposed by the Gierek regime included a shift in emphasis from production to consumption. The more phantasmal the goal, the faster that system proved unable to satiate the appetites it had awakened. Hence, numerous adverts appeared for products for which there was no need to advertise. This was undoubtedly the case with Venus being given the green light, as well.

The spontaneous response to this series of salon exhibitions dedicated to“the nude and the portrait”cannot only be understood, however, in the context of the previously postulated erotic history of the Polish People’s Republic. The demand for nudity and images of it in Polish so- ciety had never been satisfied. Erotica – not to mention pornography – clashed with the romantic vision of the nation as clean, self-sacrificing, and dedicated to a higher purpose. The pleasure of looking was mar- ginalized by a moralizing attitude, an aggressive fight against “moral corruption” and “demoralization” propagated by means of words and images (including photographs). And while it may be difficult for us to find a history of erotic and pornographic representations in Polish culture in any major publication, there is much easier to access to literature that testifies to the decades-long “war against pornography”4. This war, of course, is not being waged by the communist left (which, according to right-wing pundits, called for a “community of wives” and supported sexual libertinism during the former era), but by religious activists, primarily those associated with the Catholic church. In this sense, the social order or the class origins of Bierut and Gomulka determined the morality of the times when they wielded power to a far greater extent than did the discourse of emancipation, which today is associated with the notion of “the Left”5.

The erotic imagination, not only carnal pleasure, but its aesthetic forms as well, has never enjoyed the prestige associated with “more important” cultural topics. The triviality of the topic was not in keeping with the seriousness of art. The essential marginalization of the nude and erotica can be clearly seen not only by comparing the volume of publications by Polish researchers like Tomasz Gryglewicz or Andrzej Banach with analogous studies on the subject in Westernart6. What seems more important is the difference in the quality of the presentation, which in the local context seems forced and bland, more clumsy and awkward than appealing and inspiring. The same is true with photography. The first – few in number, but “artistic” – photographic nudes published in historical studies on the topic appeared nearly 100 years after Daguerre’s invention was brought to the Polish lands. It is hard to believe that for over a century nobody had photographed anyone – man or woman – naked. These blank pages in the history of photography in Poland themselves require their own study. During the interwar period, frivolous shows took place in an aura of fine art, while at the same time, cheap imported erotica was flooding the country. Reprints from German, Austrian, French and American magazines were the order of the day. In a country that had been liberated – morally, as well – there would be no need for “such” photos. Interestingly, the golden years for photographic “porno mags” was the Second World War, when the Germans filled the pages of collaborationist rags with reports of their progress in conquering the world, supplemented with pictures of half-naked or even nude Aryan-looking women. Jerzy Busza attributed the weakness of the postwar Polish nude, and the aversion to, among other things, occupation-era “collaboration”and attempts to corrupt the masses with cheap pleasures (meanwhile, duty calls…)7. While the Nazis made use of the attractive power of the nude to smuggle propaganda content – Aryan blonde beauties mixed with Tigers and Panthers on the frontlines fighting the enemies of the Reich – the Polish communist apparatchiks adopted a completely different policy, one devoid of charm and the aesthetics of seduction. During the Bierut era, in particular, emphasis was placed on the fight against the enemy8. Gomulka permitted extravagances like the You and I glamour magazine and, beginning with the period of the Venus salons, the regime brought back the nude as an already proven means that could be used to supplement the “propaganda of success”. In addition to exhibitions in art galleries, the nude found a permanent place in the official press; “kittens” – as Wojciech Plewiński used to call his models – began to appear not only on the pages of Przekrój, but in most popular magazines, as well.

The sexless, dull, discourse of power in Poland underwent a superficial modernization through the actions of the state organs under Gierek, who had to distinguish himself from his predecessors. This shift had an aesthetic dimension, as well as a moral one (this is why Venus became such a “moral scandal”). Permitting consumption and the enjoyment of a small, but constant surplus of goods coincided with a change in the object of desire, with the worker being replaced by the woman. The worker from Fangor’s painting now includes a slim-waisted, seductive vamp, looking scornfully in the direction of a butch-looking woman dressed in denim. The socialist woman now “had a right to be beautiful”. This postulate astounded and attracted the attention of masses of amateur photographers, including those from neighbouring socialist countries. Consumption of the female, though still socialist, body began in earnest. It is noteworthy that it is only in the context of Venus – treated as a symptom of “the consumption deviation” of Gierek – that you can see the critical potential of the manifestations of Natalia LL, Ewa Partum, Teresa Murak, Teresa Gierzyńska, and Maria Pnińska-Beres, as well as those of artists from the Repassage circle (well known to art historians, it in- cluded KwieKulik, Grzegorz Kowalski, DoGuRa, Elżbieta and Emil Cieślar).

The depictions of nude women being introduced into the main- stream culture of the Polish People’s Republic, inscribed into its hetero-normative matrix, embellished the system’s decline. However, the International Salon of the Nude and the Portrait itself did not survive socialist Poland. While Venus had its origins in one of the country’s political thaws, a fatal blow was struck to it by a boycott during martial law and the ultimate decline of the salon exhibition formula itself (amateur photographers submitting photos which were reviewed by a jury, with inners qualifying for the exhibition and receiving an award)9. After the fall of the Polish People’s Republic, the subject of erotica/pornography returned. Having acquired a ruthlessly commercial dimension, the growing industry employed many erstwhile art photographers specializing in the nude. The work of photographers who, like Wacław Wantuch or Serge Sachno, had once received laurels at Venus was now difficult to distinguish from the nudes produced by experienced amateur photographers or the professionals now working for “men’s monthlies”.

Paradoxically, relegated to the margins of artistic photography, the subject exploded in contemporary art, especially in the realms of“body art” and “critical art”, which were dominant in the 1990s. Previously as- sociated with Repassage, Grzegorz Kowalski created a sculpture studio at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts that redefined art, making it more politically and socially activist in character. Katarzyna Kozyra and Artur Zmijewski are probably the best known examples of artists using the body in art, but we should also not forget Alicja Żebrowska, Zbigniew Libera or Konrad Kuzyszyn10. Artists began to focus their activities on critiquing a society that was not so much relishing freedom as real consumption (and not simulated like under Gierek, or crisis consumption, like under Jaruzelski). A sick, old, and crippled body became a form of memento. Forced out of the shopping centre, it returned in the art gallery. With time, the subjects of sexual identity and the problems of minorities, which had so far been denied the right to be seen, began to be raised in body art. The appearance of subjects that in society, rather than in the arts, are usually designated by the awkward abbreviation LGBT can be attributed to the elaboration of a new aesthetics of representation. As Franus would say, artists offered“proposals for a new codification of the meanings of the body”that were not/male and not/female, deconstructing – to the dismay of many critics – a hetero-normative matrix that assigned sex roles according to the formula male/female. This evolution can be clearly seen in Katarzyna Kozyra’s work, which has come a long way from Portrait of Karaś (Portrety Karasia), Olympia and Women’s Bathhouse (Łaźnia kobieca) to the series In Art Dreams Come True (W sztuce marzenia stają się rzeczywistością). Male nudes and those which went beyond a simple, bipolar and hetero-normative gendered schema became a focus of attention in the art world and were exhibited in galleries. The framework of the discourse here was best described by Paweł Leszkowicz and Tomasz Kitliński’s project Love and Democracy (Miłość i demokracja), which was shown in Poznań and Gdańsk11. The male and female nude, as well as those which were non-male and non-female, once again revealed their political potential. The main concern here was the politics of the subject, the struggle for his/her identity, and hence, to this list of projects, one can add Woman on Woman (Kobieta o kobiecie) and the exhibition Boys12. Body art did away with hetero-normative sexual discourse, opening up culture to the experience of plurality and (queer) diversity. But not only.

Drawing attention to the body and the sublimation of thinking about the relationships between fantasy, erotica and art has manifested itself in recent years in projects such as Hidden Treasure (Ukryty skarb) (Warsaw, Hotel Forum, curators Lukasz Ronduda, Michal Woliński, and Piotr Rypson) and Sex Shop (BWA Wroclaw, Peter Stasiowski)13. What links both projects is an interest not only in the questions of identity and the politics of the body that characterized the practice of body art in the 1990s, but also in pleasure and pornographic fantasies. If Hidden Treasure could be contrarily called a “heterosexual coming-out” by its curators, then Sex Shop could be regarded as a “fetishistic coming-out”. The first project reminded us about pleasure that had been shut out by critical art, the second reifies pleasure, adapting ideas originally developed by the sex industry. Both projects expressed the re-evaluation that had taken place in the arts and culture, where “porn chic” had begun to dominate14. In other words, the art world – curators and artists – are affirming subjectivity by constructing a polymorphous sexuality understood as a space of the imagination with a particular kind of aesthetic appeal. Sometimes you can only wonder if these artistic fantasies can keep up with the blos- soming – in Poland, as well – market for pornography and sexual services.

1 See: A. Gogut (ed.), Akt. Album fotograficzny, Warsaw 1984; A. Gogut (ed.), Wenus Polska, Warsaw 1973.

2 E. Franus,“Narzeczona Frankensteina. Sprzeczności płci i pewien polski socrealistyczny obraz” in: Magazyn sztuki 2(10)/1996, pp. 232–240.

3 For interesting examples of the iconography of the “Soviet Venus”, of women tractor drivers or state officials who are sexy in their own particular way, see “Wieniera Sovetskaia. K 90-letiju Wielikoj Oktiabrskoj Socyalisticzeskoj riewolucyi, exhibition catalogue”, Ruskij Muziej, Moscow, 2007.

4 A good example of the struggle waged by the church against ‘new forms of social demoralization’”is a booklet by Fr. Dr. Stanislaw Bros (ed.),“The Fight Against Pornography (BiblioteczkaAkcjiKatolickiej,vol.2)”,Poznan1932,whereweread:“Inanycase,theterm ‘pornography’ is closely linked with photography. ‘Presented by the artist-painter, nudity or denudation, writes W. Noskowski, might be pornographic, or it might not be: it depends on the artist’s intention and execution. We can photograph the same model, and we get pornographic photography”, Bro. Cezary,“Kolporterki rozkładu. Kino i Radjo”, in: Ibid, p. 26.

5 Especially the “new left”, which is attacked by its critics precisely for focusing more on issues related to sexual emancipation and their cultural frames than with the economy. 6 “Sztuka a erotyka. Materiały Sesji Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki”, Łódź 1994, Warsaw 1995. Of particular interest in this volume is a text by Paweł Leszkowicz, “Ucieczka od erotyki. Seks jako strategia sztuki krytycznej. Szkic o polskiej sztuce krytycznej w latach 1960–1980”, Ibid., pp. 445–471. See also: T. Gryglewicz, “Erotyzm w sztuce polskiej. Malarstwo, rysunek, grafika”, Wrocław 2004. Worthy of particular attention is the now forgotten literature of Andrzej Banach, eg. “Historia pięknej kobiety”, Kraków 1960; “Erotyzm po polsku”, Warsaw 1974.

7 J. Busza, “Pornografia”, in: “Wobec fotografii”, Warsaw 1983, pp. 246–254.

8 Susan Sontag wrote about the sexual dimension of Nazism and the (a)sexuality of Communism in “Fascinating Fascism” in: Under the Sign of Saturn, 1980, pp. 73–105: “Right-wing movements, however puritanical and repressive the realities they usher in, have an erotic surface. Certainly Nazism is “sexier” than communism (which is not to the Nazis’ credit, but rather shows something of the nature and limits of the sexual imagination)” (p. 102).

9 Jan Maria Jackowski, who would later become a right-wing populist politician, wrote a text summing up the exhibition entitled “Nobody Really knows What You Are Like...” (photo 11–12/1984, pp. 343–348) Jackowski wrote in reference to the 15th edition of the salon about the “the struggle of the photographic camera with the recalcitrant matter of the female body.” He also wrote about its prehistory up to the student demonstrations of the 1960s (at the “Student 64” exhibition, one wall was dedicated to nudes...). He called for the “general artistic photographic rubbish heap” to be replaced by a thematic exhibition... The First National Salon of the Nude and Portrait, Venus 70 moved into full swing a few years later as an international event. The competition had its own dynamics – following its amateur beginnings, it began to include all possible photographic techniques and aesthetics (including performances reminiscent of the those of Partum and Bodo Viering), including photo media. After awarding the Grand Prix to the photographs of Tomasz Kaiser and Witold Michalik, jurors were inundated by women in various stages of pregnancy, nursing mothers, and “deeply humanistic” images of whole families... The competition had political origins, and its end must also be considered within this context – the decline of interest in the 1980s was explained by the organizers as being not due so much to the exhaustion of the formula, but rather to a “boycott”, as well as procedural problems, the lack of a catalogue, the withdrawal of its patronage by FIAP, which reduced the event’s prestige, and the repeated failure to return works that had received awards. According to Jackowski “the salons had already palled”...

10 See: I. Kowalczyk, “Ciało i władza. Polska sztuka krytyczna lat 90.”, Warsaw 2002; I. Kowalczyk (ed.), “Niebezpieczne związki sztuki z ciałem”, Poznań 2002; A. Jakubowska, “Na marginesach lustra. Ciało kobiece w pracach polskich artystek”, Kraków 2004. The link between the body and sex for artists linked with prof. Grzegorz Kowalski’s studio was expressed in an exhibition entitled Sexxx organized in 2000 in Warsaw’s Praga district.

11 T. Kitliński, P. Leszkowicz, “Miłość i demokracja. Rozważania o kwestii homoseksualnej w Polsce”, Kraków 2005. Also see the exhibition Ciepło/zimno – Letnia miłość, curator: Maria Brewińska, Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, July 11–September 10, 2006.

12 See K. Bojarska,“Chłopcy na miarę czasu”in Obieg, http://www.obieg.pl/calendar2005/ kb_cnmc.php. Bojarska rightly describes as a context for the exhibition Boys preceding exhibition projects such as Chłopaki i dziewczyny / Boys and Girls, Zachęta; Biały mazur, Bunkier Sztuki, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein; Kobieta o kobiecie, Galeria Bielska; Święto kobiet, galleries, cafes and streets in Kraków; Dzień Matki, Galeria XXI;Polka, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski; Mężczyzna, Galeria Jana Fejkiela. Each of the shows in approached the issue of gender in a unique way.

13 “Hidden Treasure”, Novotel hotel, Warsaw, September 30, 2005; “Sex Shop”, BWA Wrocław, June 1–20, 2007.

14 “Porno-chic”: a notion from Anglo-American discourse, where since the 1970s scholars like Brian McNair have been tracking the fascination with pornography in popular culture and the arts. The interaction between the culture industry and the porn industry gained unprecedented momentum in the 1990s and the early 21st century, see: B. McNair, “Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratisation of Desire”, 2002. A similar, post-feminist character could be seen in the exhibition Sexhibicja organized by the Łódź curatorial group KuRaRa on Women’s Day in March 2008 in the art studios at the Dworzec Wschodni in Warsaw.

Ewa Toniak

VIEW POINTS ON THE 70’S

When I look at the photomontages from Ewa Partum’s Self-identifica- tion (Samoidentyfikacja, 1980) series in which she, totally nude, crosses the street, stands in a queue, or blends into a crowd of women carrying shopping bags, in my mind’s eye I also see the artist Zofia Kulik,“a woman carrying bags”, running across a street in Mokotów, and jumping out from behind Partum, whose image has been pasted into the photo.

Run, Zofia, run. There’s a long road ahead of us.

Self-identification is probably Ewa Partum’s best-known series, consisting of six photomontages; in all of them, the artist poses nude in various places in central Warsaw. As she herself puts it: “Self-identification is about the places, streets and squares that were part of my daily life at the time”. Feminist critics might make a minor amendment here: these photos all concern the presence of women in public spaces. For example, in one of them, Ewa is standing beside a queue, where five women are bundled up in winter clothing. They are wearing hats and berets, carrying shopping bags and handbags, and some are dressed in high heels; the lone man in the group is lugging a mattress around with him. If not for the intervention of the artist, we would be looking at a scene typical of daily life in the Polish People’s Republic. The artist seems somehow absent, her face reveals no emotions, her gaze, directed outside the frame of the photo, is clearly distant. As in all the photos in the series, she poses nude, but in high heels.

This element of the performer’s outfit clearly irritated Zofia Kulik, especially in the context of the artist’s feminist declarations: “Well, if it’s meant to be feminism, why does Partumowa (the innocent looking -owa suffix in Polish changes the name Partum, signifying her as a woman carrying her husband’s last name) before undressing for a performance, first do her eyelashes, powder herself, and put on high heels, and only then is a “feminist”. There are so many women’s issues to sort out here”. In the 1970s, Zofia Kulik saw Partum’s actions as a performance of the masquerade of femininity.

In another photograph, Partum is again standing in a queue. Standing, and yet not standing. A queue is not the best place to pose nude. In a classical contrapposto, her body language tells us that she does not give a damn about what is going on around her. Although a micro-society has congregated in front of the pasted-in photo of the artist, a society of women, she herself seems totally alienated from them. A woman in a check coat and a beret, standing with her side to us, has struck up a conversation with another woman as they patiently queue for a taxi. Partum looks like a replicant of her. An unclothed doppelganger. A female nude coveting the gaze. The naked body is contrasted by the chequered-coated monster.

Run, Zofia, run. All that is left is “the worst stretch, from the tram stop by the zoo to the corner of Targowa and Wójcika”.

A windy Autumn day at a zebra crossing on Marszałkowska Street. While others rush along, carrying the things people usually carry; bags and shopping baskets, Ewa Partum carries herself with a dignified calm. Her high heels lift her. Ewa Tatar sees the Self-identification series as a kind of sketch for a public campaign. She ponders the medium chosen, since, as she writes, Partum could have made on-camera performances, stepping nude into the streets of Warsaw. She connects these works with a manifesto the artist announced in the ZPAF Mała Galeria. It is worth reading because it sounds as if it were written after the transformations that began in 1989: “A woman lives in a social structure that is alien to her, whose model, which is no longer suited to her current role, was created by men for their own benefit. A woman can only function in an alien social structure if she masters the art of camouflage and ignores her own personality” (emphasis mine – ET). The moment she discovers her own consciousness, which perhaps has little in common with the realities of her current life, a social and cultural problem emerges. Unable to fit into the social structure created for her, she creates a new one. This opportunity to discover herself and the authenticity of her experiences, to focus her efforts on her own problems and awareness through the specific experience of being a woman in a patriarchal society, an alien world, is the issue faced by the art movement we call ‘feminist’. It is the motivation for female artists to create art. The phenomenon of feminist art reveals a new role for women, the opportunity for self-realisation”Ewa Partum, Warszawa 1979.

Yet, in her photomontages she seems alienated from the crowd. She stands out through her nakedness which, in accordance with the canons of physical beauty, imposes a distance. If the female bod- ies at the tram stop in the black-and-white photomontages, roughly sketched out with their individual features blurred, are “anti-bodies”, Partum’s naked body restores their visibility. Their visibility as women. “Those things that are standing or running past, bundled up in winter coats, in berets, with puffy legs, with faces that are hard to remember, those are women,” she says. And she continues standing in the middle of the zebra crossing.

Ewa Tatar treats Partum’s “frozen” interventions as a political gesture, “marking the space of oppression”, within which the female subject, aware of her rights, cannot express her desires. The young feminist researcher sees Partum’s inserting of her own naked figure into photographs – that mainly depict women in their traditional, culturally accepted role as supporters, feeders, carers and other functions associated with reproduction and socialization – as a symptom of rebellion. I wonder if Partum could have seen other women on the streets of communist Warsaw. She could have. Inside taxis, for example.

Run, Zofia, run. With two baskets full of meat patties and cake, no one will recognize you in the crowd.

“Scoring oppression” in a photograph of a Warsaw street in 1980, is like a meeting with the Other. Leopold Tyrmand experienced a similar incident á rebours in 1954, which he meticulously recorded in Diary 1954, describing it as a traumatic experience. In a small shop in Mokotów, he unexpectedly encountered “the two role models for the film Adventure in Marienstadt. Female bricklayers, ladies employed in the building profession”. It is hard to understand precisely why, in a Warsaw that resembled one massive building site, Tyrmand was shocked by the presence of workers, but he reacted to them with panic. The “role model” that loomed up behind him was nothing like what was shown on the screen. The female bricklayers in the film: “looked attractive, though non-Western, lively and firm, a little burry (...) and yet clean and colourful, made for hugging and caressing”. Corporeality, its excess, and health connote a sexuality tamed through cinematic conventions, prepared for male consumption. The beginning of Tyrmand’s narration reconstructs the male fantasy concerning the “woman of the people”, whose “popular” nature implies not only the promise of erotic fulfilment, but also the availability signified by the stereotype of a woman from the “lower classes”. Their film representations, however, set in motion a train of erotic associations, while the “examples” of them encountered in the shop evoke fear and revulsion: “There was something prehistoric in them, a return to cave-dwelling, troglodytism of the female kind, not yet women, despite the painted lips and cigarettes in their fingers. Overalls, on top of them a shapeless working jacket, reveal a grim androgyny: the loss of feminine features, the clear lack of male ones, you can’t tell them apart if you don’t look in the right places, a regression to an earlier level of development, eliminated through civilization a thousand years ago, reborn under communism. They possess that special kind of ugliness of unattractive women who, fleeing from femininity, only deepen their disfigurement, becoming repugnant. Something in me is unable to believe that this thing that stood before me, on returning home, taking a bath and donning a pretty dress, would once again become feminine. Some hermaphroditism will remain”. “Ladies working on building sites” are a reminder of social decay. It is still 1954. Stalin is dead, but these ideologically constructed monsters still stalk the streets of Warsaw. Communism, as described by Tyrmand, appears as an epoch where something pre-evolutionary is being brought back to life, unaltered by the effects of civilization – the female body. It disturbs the “cognitive horizon” of the story’s narrator. It restricts access to women. A woman who, subjected to ideology turns into a bricklayer, becomes an excess, and her transformation appears irreversible. The way in which an “object of desire” is ultimately transformed into the rhetorical representation of the new ideological order is brilliantly illustrated by Wiktor Pental (1953–2000) through a female plasterer in Nowa Huta. The photographer treats the female worker from outside the categories of gender; a spot of plaster on the tip of her nose is the only indicator of the subjectivity of a woman whose hair is hidden beneath a headscarf and who has an androgynous, baggy body. Occupational emancipation, the entry into a sphere hitherto reserved for men removed the “charm created by distance and differ- ence, and imposed the woman upon men as an everyday co-worker”, something much lamented in the media in the mid-1940s. If not for the individual touches, a smile, a gaze boldly directed at the camera lens, a unique body movement, a slight lean towards the photographer, the feet together, arms behind the back, the inscription of their gender rationing the gestures of their bodies, large and small, hidden under layers of cotton drill. A photograph of eight female workers in helmets, padded trousers and overalls by Jerzy Lewczyński reproduces ideological desire in the same manner. Eight female workers as a frieze of related forms photographed against the backdrop of a scrapyard. In describing the non-carnal bodies of the female bricklayers, unaffected by culture, Tyrmand is angry. He is angry with communism. What makes Dwurnik angry thirty years later when painting his exceptionally unappealing Happy Female Bricklayer (Szczęśliwa murarka, 1988), a catalogue of cultural stereotypes about the “woman of the people” and women in general, is hard to say. Misogynistic rage is vented through an allegory of a system which is on its way out.

Run, Zofia, run. Just a few more paragraphs and we’ll run all the way to feminism and “little buzzwords”.

How could one woman look at another through the camera lens in the Polish People’s Republic? In the 1960s, Krystyna Łyczywek photo- graphed random women taking the waters in Eforie Nord in Bulgaria. Nowadays, we would describe them as having non-normative bodies, reminiscent of the heroines of Katarzyna Kozyra’s Women’s Bath house. A little out of habit, a little out of delight, Łyczywek photographed a line of female bodies plastered with invigorating mud, being warmed in the sun and set against a white wall, creating an aesthetic statement on the topic of black and white. Like Kozyra, Łyczywek instrumentalizes her heroines. But unlike her, she creates the illusion of an “exterritorial” world outside of gender, where women “do not reveal themselves”. Łuczywek’s photographs, full of nudity plastered in mud, register the female body as a politically neutral surface onto which culture begins to inscribe significance once they leave the territorial boundaries of the health spa. A crib sheet from Judith Butler. Does she look at them like a heteronormative male would look at the bodies of sexual non-objects? Or does she photograph them because a heteronormative male would not photograph them like that?

A little earlier, before Ewa Partum went out into the street, Natalia LL began to photograph herself and other women swallowing phallus-shaped and desired products in the 1970s. This activity was iconic and understandable for the 1970s. The middle of the Gierek era (1972–1975) was, according to historians, Poland’s greatest period of economic prosperity in the post-war era. According to the feminist researcher Izabela Kowalczyk, Consumer Art (Sztuka konsumpcyjna, 1972–1975) does not so much arouse the viewer’s desire to consume as it indicates the non-existence in Polish visual art of the time of certain types: the independent woman, controlling her own pleasures, aware of her sexuality. “She indicates that these are tropes of Western culture (...) which may allow women to break away from the stereotypes that function here (asexual woman) and allow her pleasure”. The liberating aspects of the series include not only its control over the male viewer and holding his gaze, but also its transgression of “socialist prudishness”. Do Partum’s photos transgress prudishness? Is manifesting approval of the normative female body and rewarding it with a gaze, while at the same time manifesting its difference, social isolation and foreignness in any way transgressive?

Natalia LL’s creativity was noticed very early on by Western feminist critics. In the mid-1970s, the artist began taking part in all the major reviews and group exhibitions, including Frauen Kunst — Neue Tendenzen in Ursula Krinzinger’s gallery in Innsbruck in 1975, where her works were exhibited alongside those of artists such as Marina Abramović, Valie Export, Rebecca Horn, and Carolee Schneemann. Ewa Partum was similarly active at the end of the 1970s. Natalia LL distanced herself from the critical assumptions of the movement and never took herself too seriously within it, although at the beginning of the 1970s it was she who Lucy Lippard saw as the leader of feminism not only in Poland, but in Eastern Europe. In a letter addressed to Natalia, she inserted Gizela Kaplan’s manifesto. Did she cut it out of the newspaper? Did she copy it out? “The philosophy of the manifesto was relatively banal and not especially insightful”, Natalia recalled in one interview. “It postulated that women needed to achieve in society that which in 1970s Poland, in a country with ‘real socialism’, we had already achieved. In our reality, apart from the difficulties of motherhood, we had already received the right to suffering, to hard work and to super-human responsibility. So, the feminists made me laugh somewhat. The convic- tion of the feminists who wanted to create their own feminist theories and art history was irritating. Seeing as they had chosen me as their representative, I refrained from criticizing their ideals”.

Does anyone remember that manifesto today? It was swept away, along with Natalia’s entire feminist correspondence on the waves of the swollen Oder River in 1987, which both literally and symbolically sealed the not over-complicated relations between Polish art and feminism. Na-talia herself recalls the manifesto with some irony, and thanks to that we have an idea of the reception to feminism in Poland in the 1970s. Incongruencies between the practices of artistic conceptualism and its theo- ries on either side of the Iron Curtain, which ressulted from differences in the traditions and significance of modernism, were termed “parallaxes” by Piotr Piotrowski.“The critical theories accompanying this art – Marxism, feminism, psychoanalysis and so on – were not discernable here”.

Run, Zofia, run. We have run all the way to “polished catch-phrases”.

Zofia Kulik, who was critical of the actions of female artists, identified feminism with a social movement, and called the declarations like those of Natalia LL and Ewa Partum “catch-phrases”: “For me, it was too little. Ewa Partum, too – feminism, feminism. When I considered their feminism, I thought: well, there’s the Women’s League in Poland, why don’t they sign up there as activists. Let them establish contacts with international organisations. Or organise something themselves and come up with some proposals”. Zofia, how could they organise and propose anything, seeing as you too had your head in the bin at the time?

Yes, run, Zofia, I’m running after you, with two bags of Wrocłaska flour.

“Throughout the whole time we lived in Praga”, Zofia recalls, and I see her as she emerges from behind Partum, crossing Marszałkowska, “more or less every other day I went by bus to Mokotów to my mother’s and brought back food. I had two special straw baskets, from which the handles kept falling off under the weight. The worst stretch was the section from the tram stop by the zoo to the corner of Targowa and Wójcik, which I had to cross with these full baskets. Everything was in there, soup, meat patties, cakes, mostly things that were already prepared because I was embarrassed to take things like raw potatoes. Mum thought it was to save us time and effort, and not that we had nothing to eat”.

Ewa Partum’s photomontages are my personal parallax: Incongruencies between theory and experience were meant to lead the reader,even in this text, to interpret them as a “spectacle of narcissism”. The communicative openness of feminist discourse on art and its history, which has surpassed the limitations of post-colonial discourse, has been considered merely in terms of loss, a phenomenon that is bewildering and unparalleled in post-war art history. And woman artists themselves – as passive and subject to alien ideologies. Agata Jakubowska has written about the “appropriation” of the works of Natalia LL by Western feminist discourse. “In the case of the works of Ewa Partum, feminism is a derivative phenomenon, something that emerges from without.” Iza Kowalczyk speaks directly of the “importation of feminist ideas.” Regardless, I am sceptical of whether, for example, Ewa Partum’s manifestos could have expected to achieve communicative fulfilment and cross the boundaries of “imitative feminism”, as I like to call the attempts to adapt Western ideology onto Polish soil in the 1970s. I do not question the actual discursive potential of the artist’s performances in the public sphere – I wrote as much not long ago. Are the empty anagrams of “appropriation”, “imitation” and “importation” suspended in a vacuum, as were once Ewa and Natalia’s works?

“Suspended in a vacuum” – this is the way Jadwiga Sawicka described Ewa Partum’s works. This could as well equally well refer to women’s art in the Polish People’s Republic; it was “like being suspended in a vacuum, or passed by, or discussed ignoring the female perspective, as if discussing their execution in this context would be demeaning, restrict our horizons. Anyway, there was no such option as the ‘feminist perspective’, so it was difficult to say that it was rejected in favour of another. (...) it seemed unattractive, silly, because it was old hat, long since worked over, the problems of equal rights, access to education and the workplace had long since been solved. Real art was happening elsewhere, not in the home, and it didn’t focus on the body, which had its own, overly specific problems, like ageing (‘my problem is a women’s problem’ said Ewa Partum, summing it up well)”. In the 1980s, this issue was taken up by Teresa Gierzyńska in the Thirty-year-old (Trzydziestoletnia) series.

Gender trouble is an authorial vision of an authorial collection, constructed around the cultural categories of gender. It was especially important for me to confront the photography of the Polish People’s Republic. Confront and recognize. The observation of how Ewa and Natalia’s creative output spars and struggles with the iconosphere of the 1970s, when the female body, sexualized and instrumentalized, a symptom of occidentalization and the creation of an image of Poland as a modern country, becomes a necessity, an essential good. The resurrected prewar nudes fit in well with the soft pornography available behind the Iron Curtain. Reduced to an object of desire, the female body gains a new application as an instrument in the struggle against “inhibitions and regression”, as Adam Mazur put it. The compulsively swallowing or melancholically withdrawn bodies of Natalia LL and Ewa Partum recover that which could never be recovered: Female objectivity.

Run, Zofia. Run.

Bibliography

Mazur Adam. Historie fotografii w Polsce 1839–2009. Centrum sztuki Współczesnej, Fundacja Sztuk Wizualnych, Warsaw 2009.

Opałka Ewa. Do trzech razy sztuka. Recenzja wystawy “Trzy kobiety”, Format, 61/2011, pp. 122–124.

Ewa Partum 1965–2001, (ed.) A. Stepken, exhibition catalogue, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe 2001

Piotrowski Piotr. Sztuka według polityki, in: Sztuka według polityki. Od Melancholii do Pasji, Universitas, Kraków 2007.

Tatar Ewa Małgorzata. Pamięć czasownika pisać. Sztuka Ewy Partum http://www.obieg.pl/ teksty/8348

Toniak Ewa. Trzy kobiety: Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Natalia Lach-Lachowicz, Ewa Partum, exhibi- tion catalogue, Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, Warsaw 2012.

Turowicz Joanna. Bunt neoawangardowej artystki. Rozmowa Joanny Turowicz, www.kulikzo- fia.pl/polski/ok3/ok3_turowicz.html